“Development by the people, of the people, and for the people,” – Angelito Manalili (1990)

“Development by the people, of the people, and for the people,” – Angelito Manalili (1990)

The need to empower the indigenous cultural communities (ICCs) or Indigenous Peoples (IPs) is a must if we want them to truly develop. The SAAD Program always has this in mind.

Crossing the public and private divide is an “inescapable part of many developmentally successful programs,” according to Peter Evans (1999). Synergistic phenomena in community development may rest into complementarity (which includes tangible and intangible inputs from the development initiators to the communities) and embeddedness (quality of social network involving the locality in building a dense social relationship) which acknowledges very important concerns on the complex nature of advancing the welfare of poverty-stricken areas, specifically, the ICCs.

The ICCs or IPs have a long history of the struggle for rights recognition, adaptability to modernization, and socio-economic progress inclusion. Some of the ICCs/IPs’ major and perpetual dilemmas have everything to do with disempowerment and sidestepped incorporation to development programs and initiatives, as well as difficulties in creating sound and relevant policies, further emphasizing subordination to the dominant population (hence, the term “cultural minorities”).

However, the constitution indicates the protection of the rights of indigenous people, conjointly prioritizing political, socio-economic, cultural preservation, and adaptation to the contemporary dynamics of communities.

In 1987, the term Indigenous Cultural Communities was introduced to the Philippine constitution, where the issues involving the minorities are seen as a topic of governance (Hirtz, 2003), seeking to assert a thorough approach on handling and crafting a space for the indigenous communities in the policy and development discourse in the Philippines and adhering to the recognition of territories and preservation of customs and cultures.

In 1997, the key legislation – Republic Act No. 8371, the Indigenous People’s Rights Act (IPRA Law) was established, declaring the recognition, protection, and promotion of Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples rights. This consists of the four bundles of ICCs/IPs’ rights which are: Right to Ancestral Domains and Lands; Right to Self-Governance and Empowerment; Social Justice and Human Rights; and Cultural Integrity.

While the IPRA of 1997 is in place, and the National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) as an institution whose primary mandate is to rally for the welfare of the ICCs is operating, forces and tensions in politics create narrow progress for the communities to be taken off the edge of poverty, accordant with the social justice provision.

Locating the ICCs in the Philippine development discourse

Despite numerous efforts in rights recognition and ICCs/IPs reform initiatives both from the state and a number of non-government agencies advocating for inclusivity in terms of development, the indigenous communities remain to be one of the most marginalized sectors in the Philippines (De Vera, 2007).

In a discussion among SAAD Project Development Officers, SAAD Director Dr. Myer Mula carefully distinguished the disparity between the general contexts of “poor” versus the “landed-poor” communities (most often the ICCs/IPs) and how miscalculations in development program implementation further widen the social gap, putting the ICCs/IPs in a disadvantaged position. He emphasized the need for exclusive, specific, and intricate response to address poverty among the indigenous communities through sustainable livelihood programs as a proactive measure.

In the case for example of infrastructure-based economic development initiatives, while it helps the general economy, the landed communities are being forced for a geographic displacement conceiving land tenure issues, which then reflects gradual depletion of access and control over natural indigenous resources due to emerging commercialization, and existing political contentions. As the communities get displaced, an array of interdependent disempowerment prevails over the present and future generations of the Indigenous Communities.

Highlighting the space for development of ICCs in the agriculture sector

However, despite the complexity of the IPs situation, there exist agencies and entities that do not abandon the pursuit of relevant reform and capacity building for the indigenous cultural communities. With the initiative of the Department of Agriculture (DA), former Secretary Emmanuel Piñol, and in line with President Rodrigo Duterte’s response to address poverty in the country, the Special Area for Agriculture Development (SAAD) Program was implemented in 2017. Two years later, Secretary William Dar took over and introduced the 8 Paradigms (New Thinking) to level up agriculture which aims to strengthen food security while addressing the sufficiency of farmers´ and fishers’ livelihood resources.

The SAAD Program caters to the marginalized and most vulnerable farming and fishing sectors living in the remote provinces in the country. The intricate program design of SAAD is a long-term investment to improve public-private engagement by empowering grass-root communities, including the indigenous people.

As of 2020, under the directorship of agriculture-scientist Dr. Myer G. Mula, the SAAD Program has continued to serve more than 17,000 identified individual farmer/fisher-beneficiaries belonging to different indigenous cultural communities in the 30 poorest of the poor provinces it covers. The program as an approach to push for impactful drop and hopefully, total eradication of poverty incidence in the agricultural sector, anchors its mechanism to contemporary framework and methods of community organizing. By using the SAAD’s four major components; (1) Program Management; 2) Social Preparation; 3) Production and Livelihood Interventions; and (4) Marketing Assistance and Enterprise Development, the program ultimately hopes to organize and transform the IP farmers and fishers from mere beneficiaries to participants and leader-collaborators of development in their community, and to cooperate to the national capacity building.

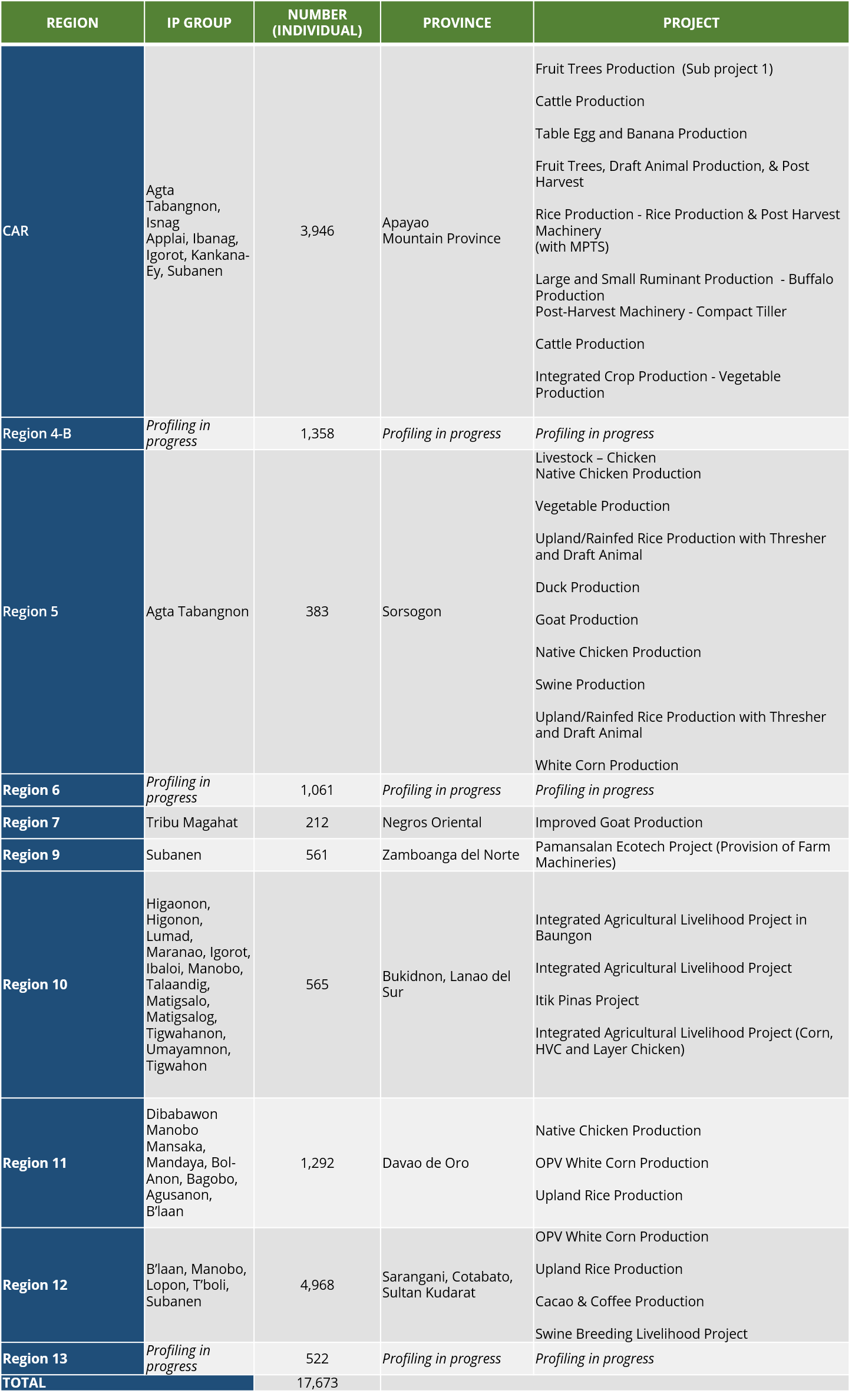

The SAAD IP beneficiaries as of 2020 come from remote provinces of CAR, Regions 4-B, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13. Some agricultural-livelihood projects that have been granted to the ICCs/IPs in the provinces since the program’s establishment include rice and vegetable production, livestock and poultry, high-value crop production, communal gardening, corn production, abaca production, aquaculture/pond culture, and farm and post-harvest machinery (Table 1).

| Table 1. | Overview of projects received by the ICC/IP beneficiaries of the SAAD Program 2017-2020 (data as of December 2020). |

Note: The table consists of a partially summarized list of interventions for the ICC/IP communities from the SAAD Program. Some regions are yet to send a complete list of ICC/IP beneficiaries, and interventions.

Note: The table consists of a partially summarized list of interventions for the ICC/IP communities from the SAAD Program. Some regions are yet to send a complete list of ICC/IP beneficiaries, and interventions.

Decentralization and empowerment

The core of SAAD Program framework lies in its Social Preparation component as a standard procedure in penetrating target communities. As contemporary theories on community organizing always emphasize: development initiative needs to be collaborative and should foster collectivity when it comes to decision-making between the initiators of development and the community members.

The concept of social preparation component is quite similar to the rapid rural appraisal (RRA) but differs significantly in the implementation. Social preparation is a long-term investment aiming to define roles with regard to the involvement and limitations of each of the actors in the whole process. The important goal is to increase the community’s social capital by enabling the community members to build a coordinated-collective leadership, which encourages independence in politics, economy, and social activities towards attaining a common goal. At the same time, the said goal sets limitation to the role of the state in terms of control, while giving space to move forward to other communities. By defining these roles, actors of development designs healthy synergistic relations in attaining one goal.

The complexity of penetrating the indigenous communities lie in the distinct customs embedded in each area. The ICCs/IPs are immensely connected with the environment and their spirituality, this is why the regional, and provincial SAAD implementers, as well as the Local Government Units (LGUs) play a key role in the program field execution as the fundamental units of organizing. These local networks are the staff that was born in the same or within the locality that actually can relate, or understand local identities and representations.

Social preparation aims to foster leadership, participation, and ownership of the livelihood programs being provided. The program offers workshops and training to enhance farmers’ capability through adapting to technological farming innovations, utilization of farming materials, imparting modern and sustainable agricultural practices, and value-adding activities to the locality’s produce. This is a pro-active approach to sustain development initiatives through meticulous apportionment of priorities to social/community capacity-building.

Standing up for ICCs

The SAAD Program interventions organizing process does not only address livelihood resources for its beneficiaries but also introduces a development perspective anchored on grass-root empowerment concepts, resounding good collective practices on leadership, participation, collective understanding, and consciousness of the state-private collaborations.

While it seems that the point at issue roots from ambiguity in policies, questionable political will, and misguided approach to development, the state and its arms, such as the Department of Agriculture continues to seek empowering programs designed for the indigenous communities in hopes to eventually lift them beyond the poverty threshold.

In essence, SAAD Program implementation always seeks to:

- Secure indigenous communities’ representation and participation in the initiated projects, while avoiding intrusion through intricate environmental and social scanning of the implementers.

- Invigorate agriculture/fishery activities to improve provincial agricultural performance.

- Provide linkages and strengthen regional, provincial and municipal local government, and members of the community to maintain access to public services.

- Organize farmers and fishers into groups, establish community/local enterprises and develop market and value chains.

- Reinforce access to nutritious, sufficient, culture-appropriate food, and food production capability of marginalized rural communities.

SAAD advances inclusivity by capacitating the indigenous communities to choose, sustain, and enhance livelihood programs. In this process, the program fosters independence and social participation among the members and implementers in the province, further strengthening social capital of the communities.

While SAAD is one of the many state-initiated programs that cater to the ICC/IPs, there is still an enormous amount of effort needed to advance the welfare of the indigenous communities in terms of policy execution in the issues of land, environment, and resource utilization and ownership.

As for the program, the experiences in immersing with the ICCs/IPs can contribute to further development, innovation, and flexibility of its implementation to fit different communities as the program progresses.

Indeed, any true development for the ICCs or IPs should be “by the IPs, of the IPs, and for the IPs.”

References:

De Vera E. 2007. Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines: A Country Case Study. PAFID Presented at the RNIP Regional Assembly, Hanoi, Vietnam on August 20-26.

Evans P. 1996. Government action, social capital and development: Reviewing the evidence on synergy. World Development, 24 (6): 1119-1132.

Hirtz F. 2003. It Takes Modern Means to be Traditional: On Recognizing Indigenous Cultural Communities in the Philippines. Development and Change. 34:887 – 914.

Labro EC, Jr. 2019. Ka-sambayanihan, Voluntary Participation and Active Citizenship. Climate Change and Poverty Reduction through Grassroots Participation and Governance, National Anti-Poverty Commission (3rd edition). pp 21-45.

NCIP Administrative. Order No. 3, Series of 2012.

Resource Persons:

Mr. Camilo A. Andi Jr., Office of the Undersecretary for Regulations

Mr. Ulysses Lustria Jr., Deputy Program Director, SAAD Program

Author: JMD Gabon, MG Mula and U Lustria

Comments (0)