QUEZON CITY, March 03, 2022 – In the five-year run of the Special Area for Agricultural Development (SAAD) Program of the Department of Agriculture (DA), it offered significant actions towards the fulfillment of its ultimate goal – to reduce poverty in the most marginalized provinces of the country.

The program puts forward, especially during the latter implementation when it activated approaches to achieve said goal, the building of local or community-based enterprises (CBEs).

This is inspired by the motivation to go beyond providing opportunities for the marginalized through agricultural grants. From household sustenance to being a source of an extra livelihood, SAAD realizes the capacity of each beneficiary and takes it a step further by organizing them into farmer groups.

Farmer groups are supposed to function as a link for the community members to create a common understanding and achieve local economic goals, through activities such as community entrepreneurial ventures. According to Peredo and Chrisman (2006), the local knowledge and cultures of the community serve as a great advantage to the groups. Understanding of local ecology, economy, needs of the community, and banking on their indigenous knowledge are significant aspects to be explored in community enterprise building.

Such activity can foster a spirit of collectivity to act and respond to the community’s needs, considering that it is manned by the community members themselves. This approach is abreast with the Department’s core reform agenda to encourage localized agricultural initiatives to work side by side with the local stakeholders to a more competitive and modernized mode of farming.

What is a CBE and why do development initiatives such as the SAAD Program integrate this as a component of growth?

In their review about CBEs, Peredo and Chrisman defined community enterprise as owned, manned, and operated by organized community members who collaborate to create market opportunities. This is aligned to the purpose of SAAD of establishing CBEs in its covered areas – to contribute to the community’s social capital (as part of a network) and incremental learning (access to extension programs).

One core concept that CBEs address is sustainability – of the project, of participation, and resources. International non-government and state-sponsored programs have a common goal of contributing to building a better economic situation for communities, led by its members.

Peredo and Chrisman however noted that some programs for the marginalized poor are usually being reduced to charity primarily because of the failure to recognize strengths of the communities, stemming from insufficient community environmental, cultural, political, and economic studies. Another factor of failure is whether consciously or unconsciously, programs are led by implementing agencies, leading to a lack of ownership from the members of the community. This then results in limited collaboration, reinforced by rewards, and subtly preserving individualism.

It is imperative for the implementing agencies to be reminded that materially disadvantaged communities are facing a higher level of uncertainty when it comes to willingness to engage in entrepreneurship and other economic ventures because of the long-term sociological effects of poverty from the individual to the community level. These uncertainties however are not innate, rather, are resulting from the unfavorable economic and political climates, and historical/cultural qualities of different communities (p. 313).

In the community’s realization of their group potential, there is hope that they will also be organized not just in enterprising activity but also in realizing and taking action to collectively demand rights and access to other social services among the community members, and their needs as a group, such as environmental welfare and cultural preservation.

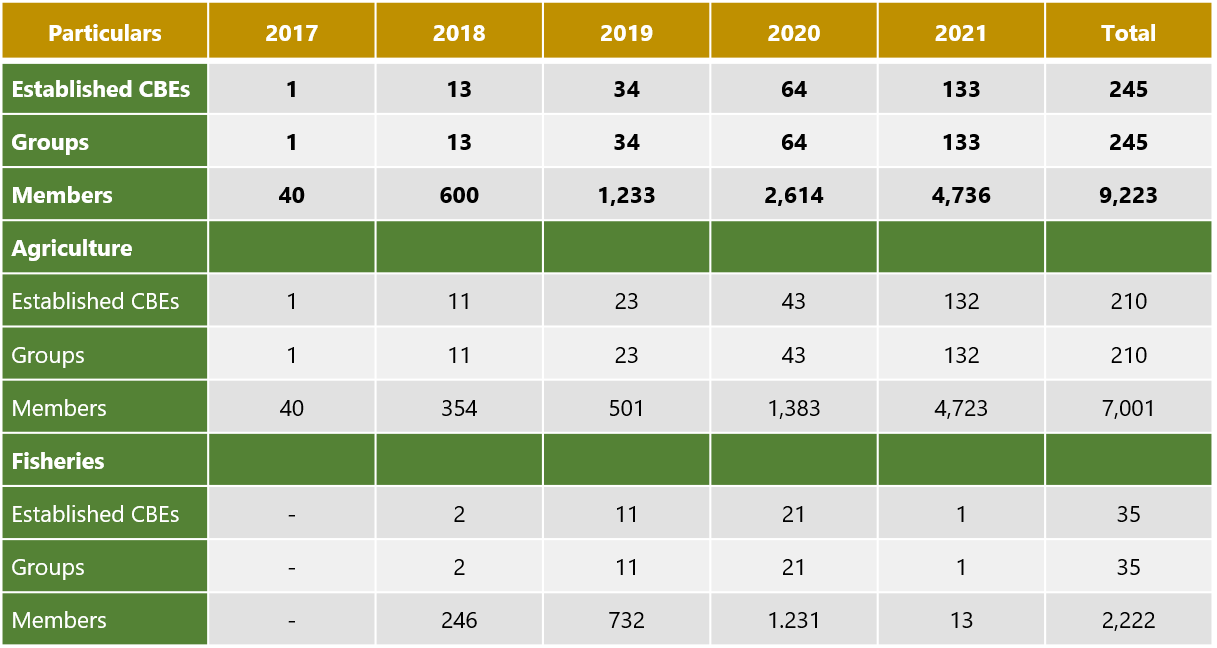

As of the 2021 record, SAAD Program activated 245 community-based enterprises in its 30 covered provinces. These CBEs are manned and owned by 245 farmer-groups, translating to 9,223 members in total. Most enterprises were established in 2021 despite the pandemic, a development attributed to years of social preparation (intersperse with capacity building) and policy strengthening by the program among the groups aimed at increasing production and productivity, leadership development, and enterprise management.

The conceptualization of marketing in the SAAD Program began in 2018, which was a huge leap from the program’s initial focus on providing food on the table. In 2019, policy strengthening and dissemination through promotion in all channels regarding enterprise building were made under the leadership of the current SAAD chief, Dr. Myer G. Mula. Capacity building through extension services is geared towards institutional convergence, farmers’ consolidation, enterprise establishment, marketing, value-adding, sustainability initiatives, and leadership. Likewise, information campaign shifted in the same context.

Table 1. SAAD Established Community-Based Enterprise (CBE) from 2017-2022

SAAD’s approach to CBE establishment calls for a program-wide effort from the field to the national implementing body. We have to come from the context that SAAD provides agricultural inputs to the identified areas for free under the basis of community assessments and preparations done with the actual beneficiaries.

Projects range from crops (food and industrial); livestock (sheep, goat, cow, carabao, horse, swine); poultry (chicken, duck, quail); machineries (farm and post-harvest equipment); irrigation facilities (i.e. solar irrigation); and fishery (aquaculture and hatchery). It also provides training and extension programs for capacity building and technical support to the beneficiaries through national and local attached agencies. To do this, the program has appointed regional and provincial staff to physically oversee the implementation. This seems to be the logical approach, but we emphasize capitalizing on the sociological and geographical edge of strengthening the networks of the community. Who else can initiate dialogues and identify or understand entrepreneurial activities of the grassroots but the people who live with or near them?

SAAD CBE’s are built based on the projects granted to the organized groups. These projects are then supported to maturate or develop until they can be considered profitable at least at the association level. Included in the development is its engagement with other agencies such as the labor department for legitimization and labor protection of the group. Members also receive extension services to augment skills in enterprise management, marketing and leadership (organizational and entrepreneurial), and conflict management. The groups are also keeping financial records, and by this time have open up a savings account.

The SAAD partially established CBEs may still receive physical support (agricultural inputs), technical and extension training in terms of association development, and market linkages. Also at this point, the partially established CBEs can be considered relatively independent in operations. While transitioning, enterprise monitoring, evaluation, market conditions, and preferences are continuously being observed by the field implementers.

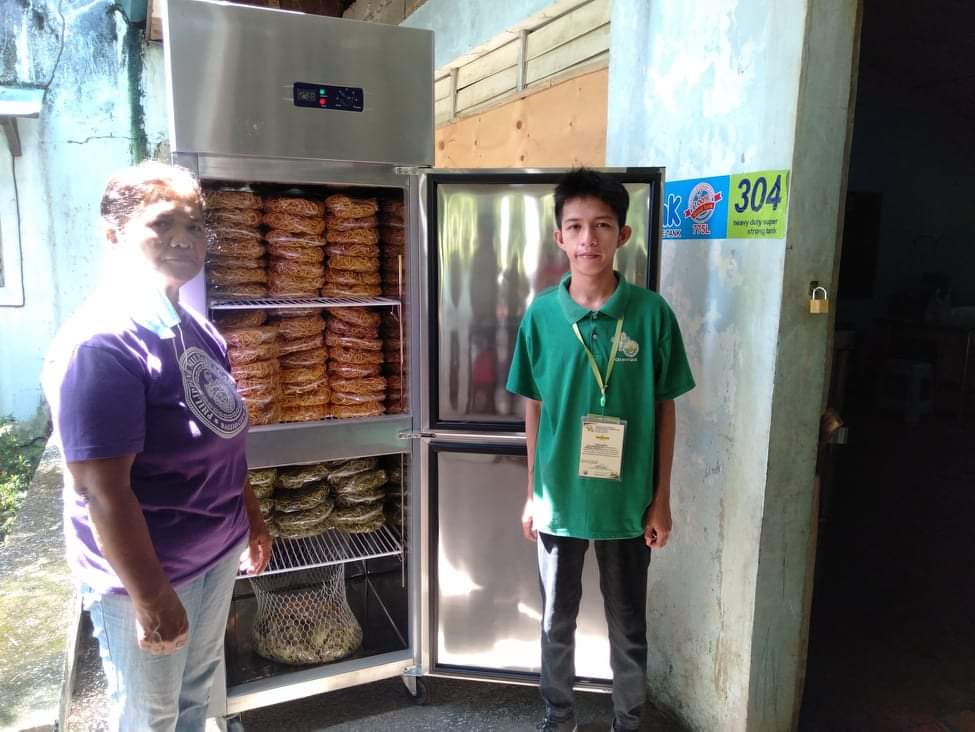

A SAAD-established CBE on the other hand, aside from its independent operations, have to be consistent with the financial flow, gaining profit, and probability of expansion. It no longer receives physical support and is on the level of expansion and branding activities.

These SAAD enterprises are unique for each group, which means that it comprises 245 farmers’ and fishers’ associations with a total of 9,223 members. From the said record, we are referring to 7,001 farmers and 2,222 fishers involved in the operations of the CBEs (Table 1).

The DA beneficiaries are involved in selling live and by-products of chicken, mushroom, processed meat, live weight pigs, peanut, corn, and fresh vegetables. Meanwhile, the BFAR beneficiaries sell live aquatic products and by-products such as finfish, bangus, kitang, seaweed, tilapia, and processed tilapia goods including longganisa and embotido tilapia, lamayo, tilanggit, and even tilapia ice cream, fingerlings, street food (fish, squid balls, and quekiam), and vannamei.

Why does SAAD promote CBEs among beneficiaries?

Value creation and innovation through local business development are essential means to alleviate poverty and preserve the natural environment. But the employment of business development as a means to overcome poverty requires an understanding of the specific socioeconomic environment in which that development is to take place,” (Peterson, 1988, as cited in Peredo and Chrisman, 2006).

Some beneficiaries are landed farmers who remain poor, and because of intersecting community positioning, layers of disadvantage lead to a lack of access to basic rights and necessities to be capable.

Director Myer G. Mula in an interview emphasized the importance of providing well-rounded projects for the marginalized beneficiaries as well as capacitating them towards more competitive production and enterprise activities.

“More than food, SAAD values nutrition and sustainability of projects of the communities. Even our fisherfolks are encouraged to expand their production, from aquaculture to vegetable, and poultry production. We also introduced abaca production which is an industrial crop. Continuous specialized training is provided such as food safety and handling, as well as continued provision of inputs, value-adding activities, and introduction to machinery, aiming to improve production and quality of produce.

SAAD’s framework aims for two desired impacts; food security, and economic relief to stability. The program operates through its regional arms who physically monitor the projects on the field, and lead the study of potential and feasible activities of the farmers and fishers. We would like to foster the native potentials and traditions and are actually helping to rejuvenate lands, and other traditional practices, only that we are trying to improve the practices that can be improved for faster and safer production,” he said.

Looking forward to the program extension, SAAD plans to execute close monitoring and evaluation dedicated to the established enterprises as part of the continued study on the stability of the CBEs under the program’s set criteria. An essential aspect of this action plan is the collaboration of the SAAD national and regional support units, other state agencies concerned, provincial and regional government units, state universities and colleges (SUCs), and most of all, the farming and fishing communities.

The continued partnerships (including international organizations) are seen to be essential to the local economic development through (but not limited to) value creation in local business establishments, alternatively as Chrisman and Pedero introduced as essential means towards poverty alleviation and natural resources protection. The SAAD Program agrees and takes actions to achieve economic development, however, sees other aspects of development (not just economic) as essential to the impactful progress of the communities.

The CBEs are also expected to establish social networks, fostering involvement and confidence among the community members to confront community issues that lead to a better understanding of the socio-economic conditions, cultural orientation, and needs of the disadvantaged population.

With these as guiding concepts, SAAD wishes to strengthen and explore community networks and potentials through continuous agripreneurial activities and gain a better understanding of the unique processes of each community towards economic development and sustainability.

Writer: Jessamae Gabon, SAAD NPMO Information Officer

Reference:

Peredo, A. M., & Chrisman, J. J. (2006). Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 309-328. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208683

Comments (0)